CANDOR (Q3.8)

Graciously Telling The Hard Truth And Demanding To Hear It From Others

Only hard Truth requires Candor

Candor is the first of the five F3 Leadership Virtues–the Habits and Ethics of moral excellence that a man must possess to be a Virtuous Leader. The Leadership Virtues are distinct from the Leadership Skills, which are the capabilities of Effective Leadership. A Leader is Effective because he possesses the Skills of Vision, Articulation, Persuasion and Exhortation (VAPE) in sufficient measure that he can Influence Movement to Advantage. However, this says nothing about his character. Only if he is also imbued with the Leadership Virtues can he be called a Virtuous Leader.

Inherent in Candor is a belief in the existence of Truth itself. Truth is a transcendental fundamental or spiritual reality that is self-evident and cognizable without further explanation. It is also immutable, in the sense that it does not change over time. What was true yesterday is true today, and will be for tomorrow evermore. A person might change, but Truth never does.

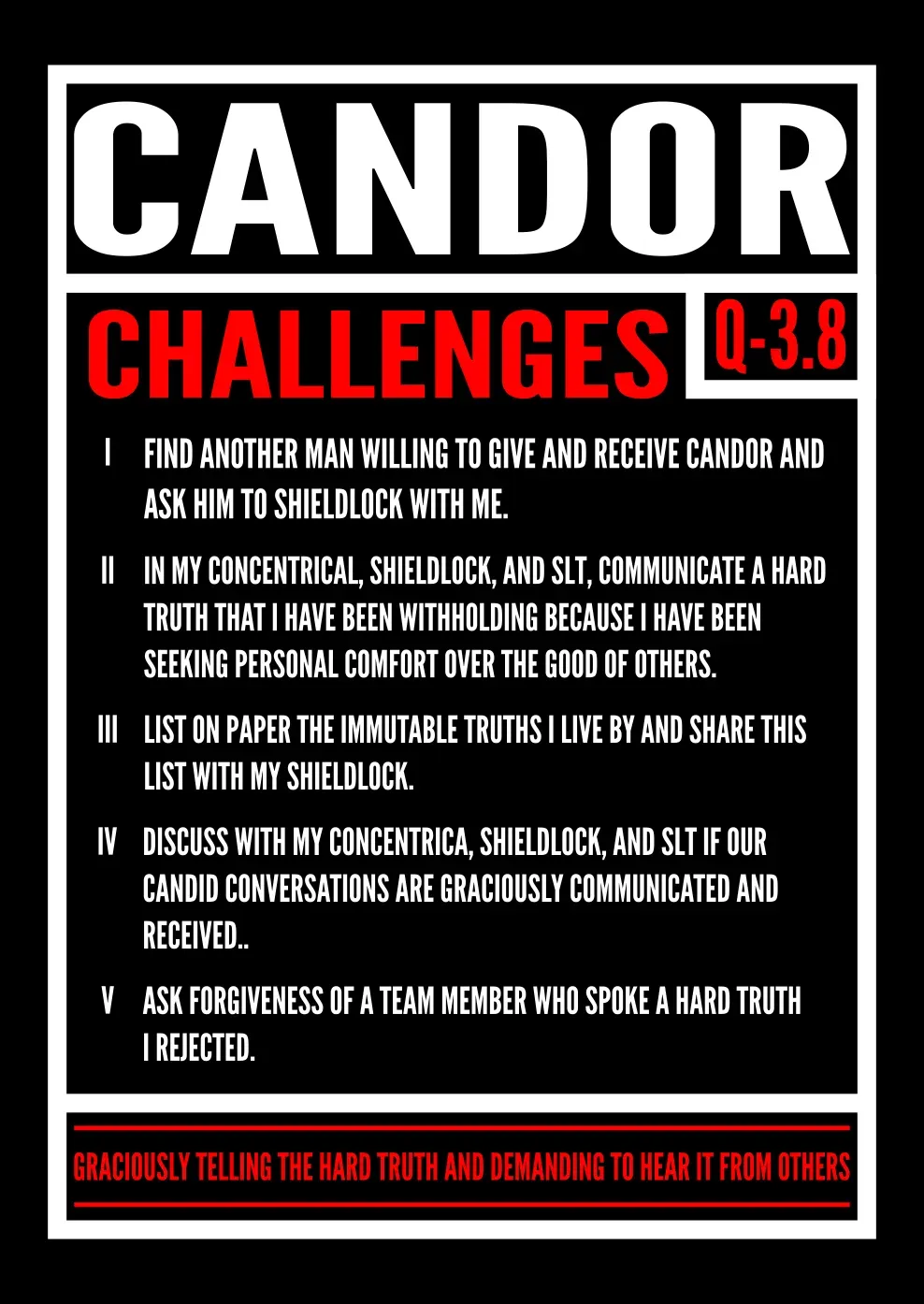

The Virtue of Candor is applicable to both universal and particularized Truths. A universal Truth has application to all or most of humankind. The fact that the Earth is round or that all organisms require water to survive are universal Truths. In contrast, a particularized Truth only effects a single person or small group of people. Drug addiction or a cancer diagnosis are particularized Truths. Their impact is limited to the person afflicted and those who are in Proximity to him. Whether a Truth is universal or particularized, Candor requires that it be disclosed by the Virtuous Leader to his followers, or by his followers to him. Candor is a two-way street.

While there are many Truths, only the hard ones require Candor. The easy Truths take care of themselves. Whether a Truth is hard or easy depends upon the effect it has on the person hearing it. If it has no impact or brings them Happiness it is an easy Truth. Telling a passenger that their flight is on time is an easy Truth. So is the fact that they have been upgraded to first class.

Easy Truths do not require character to tell because there is no particular Virtue in being the bearer of good news. Anybody can do it and most people do. Hard Truths are different, because hearing them results in Pain and Disruption rather than Happiness. Nobody wants to tell passengers that their flight is delayed or cancelled or that a loved one has died in a plane crash. These are hard Truths that require Candor to tell. Being the bearer of bad news is the province of the Virtuous Leader, because he is the only one with sufficient character to do it.

From hard Truth comes love and Trust

An Effective but un-Virtuous Leader keeps the hard Truth from his followers. He justifies his lack of Candor by couching it as a form of protection. He lies (by misrepresentation or omission) to his followers because (he tells himself) they cannot handle the hard Truth. He convinces himself that the Pain and Disruption of knowing the Truth are Hardships that only he can bear, when the reality is that he lacks the strength of character required to deal with other people’s un-Happiness. He indulges himself in that odd kind of “love” that leaves another man imprisoned in deceit rather than setting him free in Truth.

The Virtuous Leader sees no love in deceit, regardless of how well intentioned. He graciously tells the hard Truth because he knows that any Movement Influenced through chicanery will not result in long-term Advantage. Once people discover that they have been lied to, the resulting distrust will produce an Obstacle that no amount of Exhortation can surmount.

The resolve required for people to Move from the Status Quo into the relative unknown toward Advantage is fueled by their Trust in the Leader initiating that Movement. Implicit in that Trust is the belief that he has been honest about the Pain and Chaos that will be encountered on the path to Advantage. If he has misrepresented or omitted that hard Truth their Trust in him will begin to erode the moment they are forced to discover it for themselves. And once Trust begins to erode, there is almost nothing that will ever stop it.

This then is the implied consideration supporting the bargain that the Virtuous Leader strikes with those who choose to follow him: he loves them too much to tell them lies, and they Trust him enough to believe in what he says. This is the power of Candor. It engenders a bond that enables a Group to weather Hardship and turn inward to each other when faced with Chaos rather than seek the perceived high ground of their own Personal Comfort.

While a very talented Effective but un-Virtuous Leader can Influence Movement without Candor, his success will only last for a season. Eventually the chickens born of his mendacity will come home to roost, and there will be a reckoning.

Candor is a two-way street

Telling the hard Truth is only one half of Candor. The other half is hearing it. For a Leader to be Virtuous, he must be able to handle the Truth. If he can’t, than no one will be willing to tell it to him. Handling hard Truth well requires the discipline over one’s emotions that comes from Preparedness. A Virtuous Leader handles hard Truth like a Pro because he is Right, living his life in the normal and upright position.

A Virtuous Leader ensures that he will hear the hard Truth through forceful engagement with the Members of his Organization. The Gooist’s approach to engagement is to have an open-door policy and be receptive to people when they want to talk. That’s nice in theory, but way too passive in practice. Open doors and smiley faces won’t get people to spill the beans on things that scare or embarrass them. A Leader committed to getting the hard Truth knows that he will have to seek it aggressively and deal with it maturely when he finds it. He will have to ask people both what they did and why they did it, and keep asking until the answers make sense. Like most things a Leader must do, that will cause Pain.

My first battalion commander explained to me why he did this in very simple terms. He told me that he asked those questions to teach men how to make good decisions and be Candid about the Outcome. Before you act, he would say, picture yourself standing in front of my desk explaining to me what you did and why you did it–if you can’t do that very well, then you shouldn’t do what you are about to do. Rethink it. Take action in a way you can explain.

At first, because I was a very impulsive and immature Leader, I hated this. I did not like having a man twenty years older than me asking me pointed questions that I could not adequately answer. I resented the questions and the man asking them, particularly (as it often did) when the questioning took place in front of other men. But, while I didn’t like it, the process gradually led me to realize that I did not have a rational basis for much of my decision making. I didn’t think before I acted, I acted and then rationalized afterward what I had done based upon the Outcome. Being forced to explain this to my repeated embarrassment ultimately led me to change my thought process. By thinking through the explanation first–asking myself the what and why–I began making better decisions. I also started asking other men to help me with my decisions, something I was not naturally inclined to do. Looking back, I can now see that this was my initial glimpse into the power of Shared Leadership and the absolute necessity of Candor as a Leadership Virtue.

Now, thirty years later, I follow that same pattern with the people who report to me. I just ask them what they did and why they did it. At first (just like I used to do), they stammer defensively and (probably) resent being put on the spot. Often they will say, “well, I did the best I can under the circumstances”, to which I ask “do you really think so?” Usually, they shake their heads. They know. We all know. Despite the Pain, it’s a relief to get the hard Truth out there, but only if the boss takes it like a Pro.

This is where the “gracious” part of F3’s definition of Candor comes in. An Amateur flips out when he hears bad news, but a Pro takes it with equanimity, focusing more on how it impacts the Group than how it directly affects him. This requires both a Servant’s heart and stability of emotion engendered by the consistent pursuit of Joy rather than Happiness, what F3 calls Contentment (another of the Leadership Virtues).

I had a boss once who would say “I never should be surprised unless you are surprised too”. What he meant was that I shouldn’t keep bad news from him–if I knew it, he better know about it as well. That was a great policy, but it would have been nothing but a coffee mug phrase if he hadn’t backed it up with his rock-solid stability of emotion. From experience, I knew that he would not kill the messenger even if the bad news was the messenger’s fault. He took hard Truth like a Pro and focused first on Outcome management and secondarily on the root cause.

One morning, badly hungover, I had to tell this man about an idiotic gaffe I had drunkenly committed the previous night. I suppose I had some hope that it would not get back to him if I kept my mouth shut, but I trusted him and believed that I was better off confessing to him than I was surprising him. When I was done, he just shook his and said, “well, that’s not good”. Literally, two seconds later, his phone rang. I could hear whoever called him yelling in his earpiece at him for about a minute, after which he said, “that’s not the full story I heard,” and after a pause “ . . . from the man himself. He’s standing right in front of me.” In that moment, I realized that I had probably saved myself by telling my boss the hard Truth before he heard it from someone else. And, I hope, my boss realized that the reason I did it was because I trusted that he would hear it graciously, which he had.

Additional Study Materials

Socratic

Are all Truths self-evident?

Are some things better left unsaid?

What happens if you kill the messenger?

Spur

Only hard Truth requires Candor

From hard Truth comes love and Trust

Candor is a two-way street

Additional Resources

Facebook

Instagram

X

LinkedIn